KATANE TETRADRACHM image from the CNG website (www.cngcoins.com) It is my opinion that this coin is a die-struck modern fake of a Katane tetradrachm illustrating the highest quality of forgery one is likely to encounter. This opinion is based on only having seen images of the coin, and not a physical examination of the coin, but I feel the features discussed below are clear enough on the images to illustrate my discussion of the problems with this coin. I wish to make it clear that these are my opinions about this coins, and mine alone. While the images of the coin are provided via CNG's website, they had no input in the writing of this article and wish me to be clear that they do not approve or accept any of the statements I make about this coin.

The style of this coin is nearly perfect and it seems to be die linked to other known genuine examples. Normally this would be enough to confirm the authenticity, but only if the die link holds up to scrutiny, which in my opinion it does not. There are also features of how the flan cracked during the stress of striking, that are inconsistent with how such features form on genuine coins struck via hammer striking and as those are what drew my attention to this coin in the first place I will discuss them first. Flan cracks occur when the blank planchet is stressed as it expands during striking, and how those cracks form is directly related to how the coin is struck and at what temperature it was struck. Genuine Sicilian tetradrachms of this period are struck on cast planchets which come from the mold naturally annealed so the silver is as soft as it can be at room temperature, and in a rounded form like a ball slightly flattened top and bottom. The planchet is placed between two dies and the upper die is given a sharp blow with a hammer, at first compressing the metal into the dies. Once compressed, the metal may expand out somewhat, resulting in a finished coin with a typical diameter of 24 to 26 mm. Many coins show some die shift that demonstrates that more than one hammer blow is normally applied. Most Sicilian tetradrachms do not show any significant flan cracks, and it appears that the expansion out to about 26 mm usually does not create enough stress to crack the flan. On genuine specimens that do crack, what we see is usually one or two very narrow cracks extending deep into the coin, and normally going all the way through the coin so as to be visible on both the obverse and reverse. Sometimes, a few smaller cracks will also occur. This crack pattern is the result of a stress occurring suddenly under hammer impact on the metal at normal room temperature. Here is an image of a coin of this type which has formed flan cracks, in what is a normal ancient flan crack pattern consistent with a hammer strike :  (image from Numismatica Ars Classica NAC AG, auction 33, lot 67) It has one significant flan crack and one less significant one, both of which penetrate both into the coin and through the coin. I have circled in red where they are visibly doing so. There are also two smaller cracks to the left of the reverse and a larger one to the right, that do not penetrate all the way through, but appear to be related to defects from flan casting that have opened slightly during flan expansion (especially the one on the left). But what is most important is the very deeply penetrating but barely open crack in the middle right of the reverse and middle left of the obverse, which is consistent with a hammer struck coin. There are many technical problems with hammer striking, and it is not as easy as one would think. Very few people who have attempted to do so on high relief designs have actually managed to strike coins, as they cannot get the metal to fill deeply into the designs on the dies. Many forgers have not solved this technical problem so they resort to using modern presses to apply pressure more as a slower, but even squeeze, but even then, they often have to press the coins at very high temperatures (known as forging temperatures) to achieve a good strike. Striking via a slower squeeze, rather than a sudden impact, allows the metal to react differently to the stress, often forming many small die cracks around the edges that neither penetrate the coin, nor go through to the other side. Striking at high temperatures often caused the cracks to open more, but with the edges of the crack jutting out slightly, forming very sharp edges one can feel when running one's fingers over the edge. The coin under question is very unusual for this period of coinage in that the planchet is a full 4 to 5 mm wider than usual --having expanded to 30 mm diameter. There is no expectation that they made a special mold to make a broader cast planchet for this type, so if genuine, it has expanded far more than usual and has been subject to far more stress than were the 24 to 26 mm examples. If hammer struck one would expect it to exhibit one or more of the very deeply penetrating cracks that form when hammer struck coins crack. What actually happened is visible on the image below where we see a large number of very small cracks, none of which deeply penetrate the flan, or go through to the other side.

This is a typical pattern associated with the strike occurring on a press rather than via a sharp hammer blow. On the reverse we can see another crack along the upper left edge which has opened wider:

The important feature of this crack is that we can see that it has a sharp edge that juts out slightly. I have not physically examined this coin, but based on what is visible on the image, it appears that if one were to run one's fingers over the edge, that crack would feel like a slight sharp projection. Taken together, the flan crack features are consistent with a coin struck on a press at high temperature, which is a method impossible with ancient technology but easily done with modern technology. There are features on this coin suggesting that the actual flan on which it was struck is ancient. Modern forgers, wanting their product to stand up to a metallurgical analysis, have been known to use worn examples of genuine coins as their planchets, so that the alloy will be correct. It is important to remember that genuine examples of this type are normally only 24 to 26 mm diameter, and this example is 30 mm. Starting with a genuine coin already expanded to about 25 mm, and then subjecting it to further expansion by pressing with great force and possibly high temperature, the expansion to 30 mm is thus possible. The next consideration is an apparent die match that might prove the coin authentic. For this, we must compare it to an actual coin from the same set of dies, for which there is no reasonable doubt of its authenticity. The best specimen available for this purpose is one known as the Berlin specimen, which was de-accessioned from the Berlin Königliche Münzenkabinett as a duplicate and sold by A. Heiss on their behalf in 1902. This provenance, going back to 1902, and the encrusted somewhat uncleaned nature of the coin, leaves no doubt that it is an authentic specimen of the type suitable for this study:  (image from the CNG website, www.cngcoins.com) To establish the obverse die link, I have provided this image of the coin under discussion over laid by a 50% transparent of the Berlin specimen :

Where the designs are an exact match, they disappear into each other, while differences show as fuzzy areas and, if the different is major, as two distinct features on top of each other. There is a distinct difference along the left side of the cheek, but it appears to result from the coins having been photographed at slightly different light source angles, or is possibly due to a minor distortion during striking. But what is important is that for about 98% of the design there is a nearly exact match, which no ancient die cutter working by hand could do on two different dies. This proves that both coins appear to be struck from the same obverse die. To establish the reverse die line is slightly more difficult. When ancient coins are struck it is normal for there to be two or more hammer blows. The obverse die is fixed, and generally the coin will lock into it during striking, but the reverse die is not fixed and can bounce slightly during hammer striking and may come down in a slightly different position between the strikes. This results in what is known as die shift and can result in some distortions to the designs during striking. There are related problems that occur during modern pressing if the press is applied more than once, but they look similar. I have provided two 50% transparent overlay images of the Berlin specimen over the coin in question to take this distortion into account. TThe first is aligned across the horses' heads and driver’s arms where the designs are a near perfect match, although due to minor die shift, there is a clear discrepancy in the lower half most easily seen where the two ground lines do not overlay each other:

The overlay image below, aligned on the ground lines, demonstrates how there is also a near perfect match on the lower half of the coins, with every letter in the inscription being a perfect match. There can be no doubt that the two coins also appear to share a common reverse die.

With the apparent die match established and with no question that these are struck and not cast coins, there are two possibilities: first, and which is widely accepted for this coin, is that the match proves the same set of dies, and since the Berlin specimen it is matched to is certainly authentic, both coins have to be authentic. The other possibility, which I believe to the case, is that a genuine coin struck from these dies was used by a modern forger as a model from which to create new dies that nearly perfectly matched the original dies, and this coins is a modern fake from those modern dies. The method by which modern forgers manufacture such dies is known as hubbing. An impression of the genuine coin is taken, capturing all major and nearly all minor features of the original coin that give a coin its artistic style. But hubbing does not capture every tiny detail accurately. Sometimes small distortions are introduced, and often on genuine coins some features are off the flan edge or weakly struck and so are not present to be transfered. The forger must then touch-up his new die by hand cutting missing details. It is nearly impossible to do that touch-up work perfectly, and it is the mistakes that the forger makes or fails to correct that usually gives him away. The smaller details, and details around the edges that might have been off the flan on the genuine coin, are the best places to look for these discrepancies. Below are images are the Nike figure as it appears on the known authentic Berlin specimen (top) above the new specimen (bottom) :

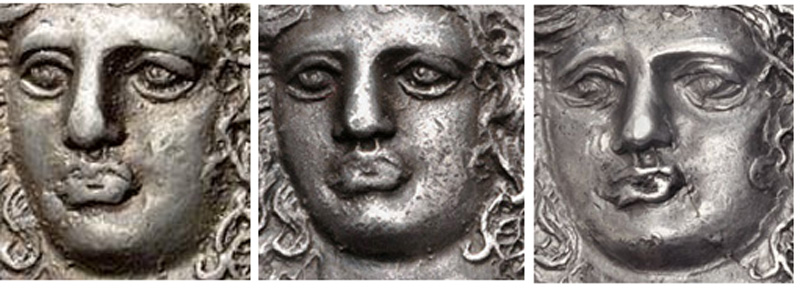

On the Berlin specimen the feather details of the wings are very delicate; Nike's head is finely engraved with a clearly female appearance, and her gown looks sheer, following her curves, showing a narrow waist and well-rounded posterior. Note that the double cheek appearance of her posterior on this example is actually due to a minor die shift and does not appear that way on all genuine specimens, but the rounded form does. Clearly, this is the work of a master engraver. On the lower image, the feather details are coarser in a way that cannot be explained by die shift. The line of dots on her wing extends down to her shoulder, with each successive dot becoming larger. This is very different from how they look on the authentic Berlin specimen and I have checked this on other specimens from this die and it is clearly not what was on the original die. On this new example, Nike's head, which is very finely engraved on the Berlin specimen, is little more than a lump which is not even clearly human let alone female. Her gown is now much heavier, hiding her female lines and no longer revealing her rounded posterior and thin waist. These differences appear to be consistent with a combination of distortions in the die hubbing process and with a forger doing touch up work to an imperfectly hubbed false die. Now let us turn our attention to the obverse die. The three faces below come from three different coins. The Berlin specimen is in the middle, the one from above used to show the genuine style flan cracks is to the left, and the specimen under discussion to the right:

The first thing to look at are the eyes, where the two examples to the center and left are very finely engraved, giving the face a natural almost life like look with an intense stare. The example on the right, in spite of it being a much better struck and less worn example, has a less lifelike look and that intense stare has become a dull glazed-over look. This difference is primarily because the very sharp pupil in the eyes of the examples to the left are only a vague dot on the example to the right. These pupils are one of the smallest features of the coin, and not easily transferred while hubbing a false die, which is the most likely explanation and the forger missed doing that touch-up. The form of the mouth is another problem. On the two genuine examples to the left the mouth is slightly distorted but if you look closely the mouth on both specimens has been slightly distorted by wear and by the die not fully filling there giving it a thickened appearance. However, the overall lines still have a relatively natural outline as the die cutter would have intended. In David Sear's Greek Coins and Their Values, 1978, Volume 1, p. 81, there is a picture of the British Museum specimen of this type, which I believe is the the best struck and highest grade example from the non-retouched die. It does not exhibit a distorted mouth, but rather shows us exactly what it looked like as the ancient die cutter intended. I have not been able to locate an image of the actual coin I can use for this page, but I do have this image of that part of the design on a Robert Ready electrotype done from their example which shows the details fairly clearly. One can easily see that the form of the mouth is not distorted when both well struck and not very worn:

The coin under discussion is on the right of the three-face image above. It is a near perfect strike with almost no wear and so the lips on it represent how they were engraved into the die from which it was struck. Clearly, they are not the same as on the authentic die from which the other two plus the British Museum example were struck. This is clear evidence the coin in question was struck from a die in which a modern forger "improved" details on his hubbed die, without understanding the true nature of what he was improving. There is a second example known from this false die, also high grade and nearly unworn, and it also shows the lips with this distortion --confirming that this feature was in the die. Having looked at as many images of this type as I could locate, they have two features in common to all but those from the retouched dies.

The first is that on the obverse they are strongest in the center and weaken towards the edges, which is most noticeable on the inscription on the right edge. The image above used to show the genuine flan crack pattern also shows this clearly. This happens because these coins are struck on rounded planchets which must expand between the dies as the coin is struck. Contact is initially the center of the flan against the center of the die. As the coin forms between the dies and the flan spreads, the die pressure dissipates, and so die pressure is at its highest as the centers form, and at its lowest as the outer parts of the design form. Looking at the coin under question, the designs are of roughly of equal strength across the entire design, including on the inscription near the edge. This shows a constant die pressure throughout the strike, and while inconsistent with an ancient hammer strike technology, it is consistent with pressing on a modern press. The second is much more difficult to prove as there might be images somewhere of coins that are struck from the original, not retouched dies, which will show all of the details, but as yet I cannot locate such an example. All the examples I have found exhibit two patterns of weakness in the strike: on the obverse the laurel leaves on Apollo's forehead are slightly flat at the highest point, that on the nicest examples, seems to be related more to the die pressure not being able to fill those details on the die than to wear. Apollo's lips are poorly formed and thickened, and his nose tends to be slightly broader than one would expect, also resulting partly from weak strike, with the only exception to the lips being on the British Museum specimen which is the best struck of them all. On the reverse there is poor detail on the horse heads with no specimen showing the eyes of the closest horse, and various degrees of detail on the other horses. Even on the best struck and least worn example (the British Museum specimen) there is no detail on that closest horses' head (as illustrated on page 81 of volume 1 in David Sear's 1978 edition of Greek Coins and Their Values). Since the obverse of that specimen shows nearly no wear, that lack of detail on the reverse cannot be due to wear. Clearly, the ancient minters could not achieve enough detail to fill all the details on this very deeply cut die. This might be why only one die of this particular design was cut, and all other dies have a slightly different design on which Nike flies over the horse, and the horses do appear in lower relief (although I have not actually measured them, and state this based on how they appear on images). The only exceptions I have so far seen are on two examples, both from the retouched dies, both exceptionally evenly and well struck in a way not consistent with the hammer striking technology of 5th century BC Sicily. There are some who would argue that the dies were re-cut in ancient times to improve striking quality, but as the problem is a design cut too deeply into the die, the solution would be to reduce that depth of engraving. That would not be a simple thing to do: they would have to shave down the fields, but that would remove all the shallowest details such as the inscriptions which would then have to be re-cut. But the overlay images above prove that was not done to this touched-up die. So what remains is that these coins were struck at a die pressure higher than the ancient minters could achieve, which again points to modern minting technology. When presented with this body of evidence, the conclusion I find I must come to is this coin was struck from a false hubbed a retouched die and is thus a modern fake. The question then must be asked, which of the genuine coins was the host coin from which the false die was hubbed? At this point the only genuine specimen I can locate that is well enough struck and centered to have been used, is the British Museum specimen mentioned above. There is no possibility the forgers had direct access to that coin, Nor is there any possibility anyone in the British Museum was directly involved in this type of forgery. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Robert Ready worked at the British Museum making high quality electrotype copies of their more important coins, including their example of this type. In the 1980's and 1990's a number of high quality fakes were accepted as genuine and sold at major auctions, but were later identified as fakes and it was determined many were from dies hubbed from British Museum eletrotypes. They became known as the British Museum Forgeries (and please note the British Museum was in no way involved in the forgery). I believe this Katane tetradrachm, struck from these retouched dies, belongs on the list of the British Museum Forgeries. While the opinions about this coin on this page are entirely my own, I do appreciate the help provided to me by Jorg Lueke who aided in finding suitable examples and images of various specimens which helped in my observations, and whose comments and questions assisted me in determining what details needed to be discussed. Back to examples of fakes.Top of Page

|